Manufacturing Engineering Challenges of Pharmaceutical 3D Printing for on-Demand Drug Delivery - Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers - Open Access Journal of Engineering Technology

Abstract

There are about two dozen 3D printing technologies

available in the market. These technologies differ in terms of layering

mechanism, type of material that can be handled, binding mechanism and

suitability for solid dosage form manufacturing. Based on literature

information and preliminary data, fused deposition modeling (FDM),

selective laser sintering (SLS) and powder-bed 3D printing methods have

emerged as the most promising candidates for delivering on-demand drugs

according to established Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) guidelines of

the pharmaceutical industry. However, information on interplay of

critical process parameters (CPPs) and critical materials attributes

(CMAs) on the critical quality attributes (CQAs) of the formulations and

products that will determine their in-vitro and in-vivo performance is

not readily available in the literature. Through this mini-review, we

underline the pressing need for the systematic exploration of these

critical factors and present the Ishikawa diagrams for the three

mainstream 3D printing techniques already penetrating the specialized

niches of the pharmaceutical manufacturing market at an extremely fast

pace.

Keywords: Additive

Manufacturing; Critical quality attributes; Compatibility; Fused

filament fabrication; Micro particles; Nan particles; IngredientsAbbrevations: AM: Additive Manufacturing; FDM: Fused Deposition Modeling; FFF: Fused Filament Fabrication; SLS: Selective Laser Sintering; PVA: Polyvinyl Alcohol; CPPs: Critical Process Parameters; CQAs: Critical Quality Attributes; CMAs: Critical Material Attributes; GMPs: Good Manufacturing Practices

Introduction

Additive Manufacturing (AM) in general and

three-dimensional printing (3DP) in particular is emerging technologies

expected to revolutionize pharmaceuticals manufacturing along with other

fields [1-4]. These technologies offer the ability to create limitless

dosage forms that are likely to challenge conventional drug fabrication

methods not only in product quality and efficacy but also in cost

efficiency as 3D printers have already been successful in producing

novel dosage forms within minutes [3]. Three situations where this

on-demand pharmacy capability may be applicable include printing

directly on the implants or tissue scaffolds, printing “just in-time” in

healthcare facilities or in other resource-constrained settings and

printing low-stability drugs for immediate consumption. In all these

scenarios, 3D printing technologies provide attractive solutions to

explore on-demand pharmacy [5]. FDA approved first commercial drug

product based on 3DP technology in 2015 (NDA #207958,

Spritam® (levetiracetam) triturates Aprecia Pharmaceuticals Co) [6]. It

is a high drug loaded tablet that disintegrates in less than 10 seconds

which is atypical even for orally disintegrating tablet. Even though its

underlying manufacturing technology is two decades old, very little

information is available in the public domain about the process and

formulation variables that could affect critical quality attributes of

drug products manufactured by 3DP. Furthermore, quality defects in the

drug products manufactured by 3DP will be entirely different from

compressed tablets. Thus it is essential to evaluate 3DP techniques for

their compatibility with pharmaceuticals from the perspective of

on-demand pharmacy feasibility and application.

3DP Technologies Amenable to Pharmaceutical Manufacturing and Their Unique Aspects and Materials

The primary 3DP technologies that can be used for

pharmaceuticals manufacturing are inkjet-based or inkjet powder-based

3DP, fused deposition modeling (FDM) also called

fused filament fabrication (FFF) and selective laser sintering

(SLS).

Inkjet-based or inkjet powder-based 3DP

Whether another material or a powder is used as the

substrate is what differentiates 3D inkjet printing from powderbased

3D inkjet printing. In inkjet-based drug fabrication,

inkjet printers are used to spray formulations of medications

and binders in small droplets at precise speeds, motions, and

sizes onto a substrate. The most commonly used substrates

include different types of cellulose, coated or uncoated paper,

microporous bioceramics, glass scaffolds, metal alloys, and

potato starch films, among others [2-5]. Researchers have further

improved this technology by spraying uniform “ink” droplets

onto a liquid film that encapsulates it, forming microparticles

and nanoparticles. Such matrices can be used to deliver small

hydrophobic molecules and growth factors [7]. In powder-based

3D printing drug fabrication, the inkjet printer head sprays the

“ink” onto the powder foundation. When the ink contacts the

powder, it hardens and creates a solid dosage form, layer by

layer. The ink can include active ingredients as well as binders

and other inactive ingredients. After the 3D-printed dosage form

is dry, the solid object is removed from the surrounding loose

powder substrate [3-5,7]. Very limited work has been reported

concerning controllable printing parameters in binder jetting

process and materials attributes (active and inactive), which

could substantially affect critical quality attributes (CQAs)

of pharmaceutical formulations. Therefore, having a good

understanding and experimental insight into the practical effects

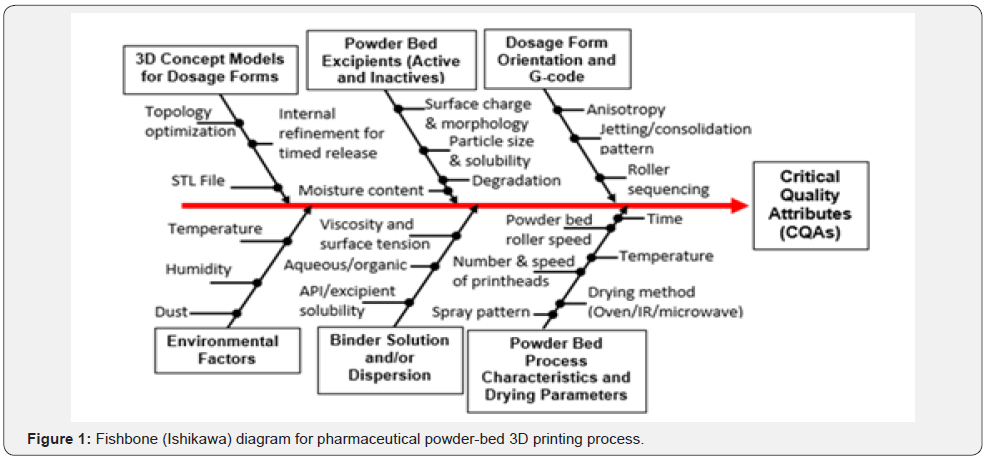

of such parameters on CQAs seems to be essential. The fishbone

(Ishikawa) diagram for pharmaceutical powder-bed and inkjet

3D printing processes is given in Figure 1.

Fused deposition modeling (FDM)

In FDM/FFF, the object is formed by layers of melted or

softened thermoplastic filament extruded from the printer’s

head at specific directions as dictated by computer software.

Inside the FDM printer’s head the filament is heated to just above

its softening point which is then extruded through a nozzle,

deposited layer by layer immediately followed by solidification

[4-5,7-9]. The speed of the extruder head may also be controlled

to stop and start deposition and form an interrupted plane

without stringing or dribbling between sections although

nanoparticle emissions were detected during the process

[2-3,9-12]. The potential of FDM 3D printing to incorporate

drugs into commercially available filaments has been explored

previously [13,14]. Nonetheless, all those studies highlighted

several challenges involved in employing printing technique for

pharmaceutical applications. The use of elevated temperatures

(185-220 °C) and limited drug loading (0.063-9.5%w/w)

renders it less suitable for many drugs particularly thermolabile

ones [13-15]. FDM 3D printing has been also restricted to a

number of biodegradable thermoplastic polymers such as

polylactic acid (PLA) [16] and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) [4,13-

15] in comparison to a wide variety of choices for conventional

tableting. Despite the attractive properties of PVA [17] and PLA

[18], the use of high polymer ratio in combination with the need

for high molecular weight of the polymers generates polymeric

matrices with limited porosity, thus resulting in extended drug

release patterns. To increase the flexibility and potential of FDM

3D printing process, never filament formulations also employing

nanocomposite compounding approaches will be needed to

overcome existing limitations of FDM type pharmaceutical 3D

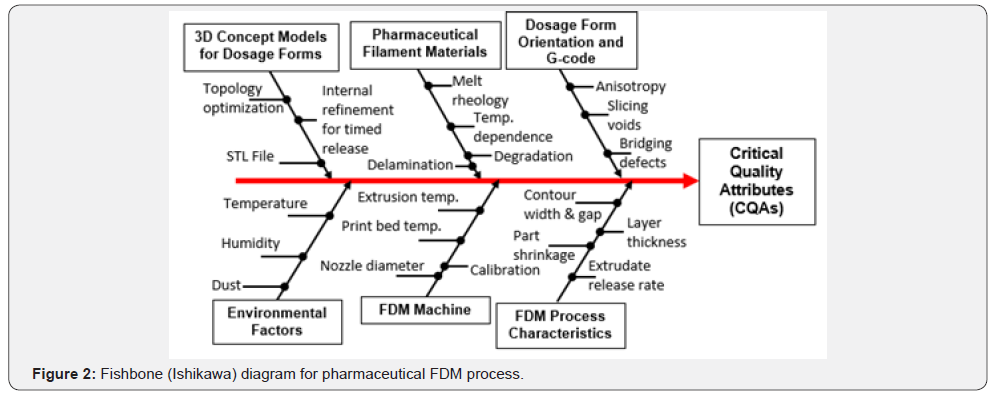

printing. The fishbone (Ishikawa) diagram for pharmaceutical

FDM processes is provided in Figure 2.

Selective laser sintering (SLS)

Like all methods of 3D printing, an object printed with the

SLS process starts as a CAD file. Objects printed through this

method are made with powder materials, most commonly

plastics, such as nylon, which are dispersed in a thin layer on top

of the build platform inside an SLS machine. The laser heats the

powder either to just below its melting point (sintering) or above

its melting point (melt consolidation), which fuses the particles

in the powder together into a solid form. Once the initial layer is

formed, the platform of the SLS machine drops usually by less

than 0.1 mm, thus exposing a new layer of powder for the laser

to trace and fuse together. This process continues again and

again until the entire object has been printed [2,19]. Very limited

information is available in the literature for pharmaceutical

application of the SLS technique [5,20]. The characteristic

limitations of this process are attributed to incompatibilities

between laser energy settings and properties of thermoplastic

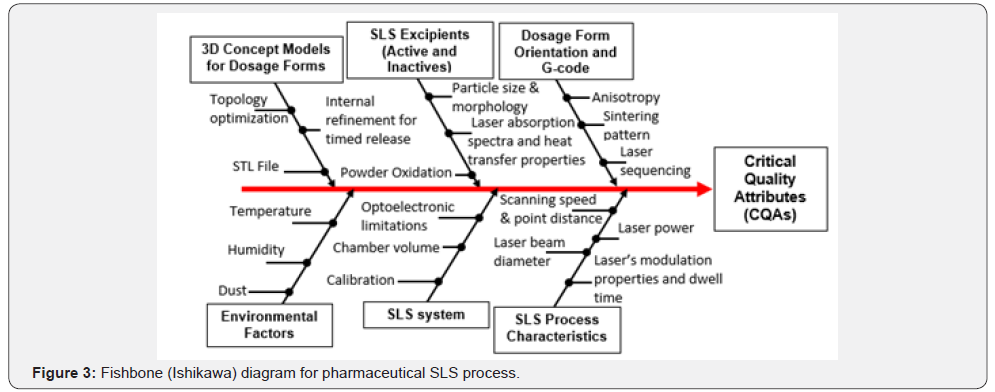

polymer used to print drug product. It is important to understand

the interplay of the SLS critical process parameters (CPPs) and

polymeric powder critical material attributes (CMAs) on critical

CQAs, as shown by the Ishikawa diagram in Figure 3.

Conclusion

The most promising 3DP technologies for pharmaceutical

applications and their manufacturing engineering related

challenges were discussed. In all methods, understanding

critical process parameters (CPPs) is equally important as

understanding critical material attributes (CMAs) to ensure

consistent quality of 3D printed solid dosage form. Rigorous

experimental studies are needed to validate process and materials

engineering correlations between CMAs and CPPs, which can

also identify optimal control strategies and potential risk factors

for process failure or deficiencies in terms of pharmaceutical

good manufacturing practices (GMPs). Including all variants

and hybrid approaches, about two dozen 3DP technologies

currently exist in the market each with varying capabilities and

complexities. Although objective assessments of current process

limitations and capabilities assign a higher chance to powder bed and SLS techniques in the race for on-demand drug delivery,

the Darwinian dynamics of technology evolution coupled with

process engineering and materials technology innovations will

determine which particular ones would be indeed the fittest to

survive in the domain of pharmaceutical manufacturing.

For more articles in Open Access Journal of

Engineering Technology please click on:

Comments

Post a Comment